Bilingualism modulates domain-general functional connectivity: insights from resting-state electroencephalogram

Alex Sheehan, Doug Saddy, Christos Pliatsikas

University of Reading

Previous bilingualism research indicates that one’s degree of bilingual experience dynamically impacts cognition, brain structure, and function. This is demonstrated by increased performance amongst bilinguals in behavioural tasks in the language and executive control domains1–3, changes to brain structure in regions associated with language and executive control4–6, and alterations to brain function and connectivity in resting-state electroencephalography (EEG) studies7–9. These findings include increased posterior activity compared to monolinguals, increased interhemispheric connectivity, and increased long-distance communication as experience increases. The BAPSS model of bilingual functional brain development suggests that these patterns indicate that bilinguals begin to rely less on frontal regions, and more on posterior and subcortical regions as experience increases10. The aim of this study was to determine how degree of bilingualism interacts with domain-general task demands to impact whole-brain functional connectivity. The study used a novel task-driven resting-state EEG paradigm, using the short-term variability of resting-state connectivity to measure the patterns of connectivity both pre- and post- a cognitively demanding task. We used the Language and Social Background Questionnaire to assess demographics and degree of bilingualism11.

The task used was a serial reaction-time artificial grammar learning task designed to assess hierarchical structure representation and implicit statistical learning. This is a very generalised higher cognitive ability so is considered to be cognitive domain-general, with bilinguals having been found to perform better than monolinguals on this task12. We used a binary Lindenmayer grammar which follows the Fibonacci sequence13, presented to participants as red or blue circles on the screen, to which they must respond indicating which colour they were just shown14. We analysed the data using Generalised Additive Models – a non-linear modelling method – modelling LSBQ composite score against connection strength between multiple regions of interest. The connectivity patterns were then compared to assess any differences between the at-rest and post-task states.

Pre-task, level of bilingualism showed a significant relationship with the connectivity strength between long-distance (e.g., frontal-parietal), inter-hemispheric, and intra-hemispheric connections – a total of 4 significant connections affected by level of bilingualism. Our post-task recordings yielded 10 significant bilingualism-modulated connections – involving multiple long-distance (e.g., parietal to frontal; central to occipital), inter-hemispheric, left temporal, and medial occipital region connections. Crucially, the post-task connectivity analysis revealed new bidirectional interhemispheric temporal connections, and an increase in the number of total connections to occipital and left temporal areas. These findings are compatible with the BAPSS model, indicating that linguistic experience affects the brain regions recruited to complete the task at hand – involving greater occipital, temporal, and interhemispheric connectivity, particularly during task-based cognition. We propose that this is due to the increased control demands in bilingualism, leading to increased efficiency of automatic monitoring processes, and thus greater strength of functional connections in regions enlisted for these demands. The clustering of connections around the left temporal region post-task is particularly unexpected. This suggests strong language network activation despite no language being present in the task.

1. Calvo, A. & Bialystok, E. Independent effects of bilingualism and socioeconomic status on language ability and executive functioning. Cognition 130, 278–288 (2014).

2. Akhtar, N. & Menjivar, J. A. Chapter 2 – Cognitive and Linguistic Correlates of Early Exposure to More than One Language. in Advances in Child Development and Behavior (ed. Benson, J. B.) vol. 42 41–78 (JAI, 2012).

3. Prior, A. & Macwhinney, B. A bilingual advantage in task switching. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 13, 253–262 (2010).

4. Pliatsikas, C. Understanding structural plasticity in the bilingual brain: The Dynamic Restructuring Model. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 23, 459–471 (2020).

5. Korenar, M., Treffers-Daller, J. & Pliatsikas, C. Bilingual experiences induce dynamic structural changes to basal ganglia and the thalamu. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1017465/v1 (2021).

6. Olsen, R. K. et al. The effect of lifelong bilingualism on regional grey and white matter volume. Brain Res. 1612, 128–139 (2015).

7. Grundy, J. G., Anderson, J. A. E. & Bialystok, E. Bilinguals have more complex EEG brain signals in occipital regions than monolinguals. NeuroImage 159, 280–288 (2017).

8. Bice, K., Yamasaki, B. L. & Prat, C. S. Bilingual Language Experience Shapes Resting-State Brain Rhythms. Neurobiol. Lang. 1, 288–318 (2020).

9. Pereira Soares, S. M., Kubota, M., Rossi, E. & Rothman, J. Determinants of bilingualism predict dynamic changes in resting state EEG oscillations. Brain Lang. 223, 105030 (2021).

10. Grundy, J. G., Anderson, J. A. E. & Bialystok, E. Neural correlates of cognitive processing in monolinguals and bilinguals. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1396, 183–201 (2017).

11. Anderson, J. A. E., Mak, L., Keyvani Chahi, A. & Bialystok, E. The language and social background questionnaire: Assessing degree of bilingualism in a diverse population. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 250–263 (2018).

12. Vender, M., Krivochen, D. G., Phillips, B., Saddy, D. & Delfitto, D. Implicit Learning, Bilingualism, and Dyslexia: Insights From a Study Assessing AGL With a Modified Simon Task. Front. Psychol. 10, (2019).

13. Krivochen, D. G. From n-grams to trees in Lindenmayer systems. ArXiv210401363 Cs (2021).

14. Schmid, S., Saddy, D. & Franck, J. Finding hierarchical structure in binary sequences : evidence from Lindenmayer grammar learning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/fp5zb (2022).

Biliteracy and L2 proficiency modulate reading strategies and reading-related skills in late L2 learners with and without dyslexia

Ilaria Venagli1,2, Theo Marinis1, Tanja Kupisch1

1 University of Konstanz

2 University of Verona

ilaria.venagli@uni-konstanz.de

Background. The consistency of grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPC) modulates reading strategies. Monolingual readers of transparent orthographies (consistent GPC) may favor the processing of small grain size units (e.g., graphemes) given their consistent correspondences. Conversely, readers of more opaque orthographies (inconsistent GPC) rely on larger grain size units (e.g., bigrams, or trigrams), in that they are more consistent than smaller units [1]. Studies on biliteracy effects in early bilinguals, considering the exposure to both transparent and opaque orthographies, have shown that reading strategies are modulated by cross-linguistic interactions [2]. It remains unclear whether late bilinguals adapt their L1 reading strategies to the target language [3] or develop hybrid strategies [2] as an effect of the experience with two different orthographies. Additionally, it is unclear whether such orthographic-specific cross-linguistic interactions modulate reading strategies in L2 learners with developmental dyslexia (DD).

Goal. This study investigates how the development of proficiency in an opaque late L2 (English) affects the reading strategies of late L2 learners (with and without DD) whose L1 has a highly transparent orthography (Italian). This is investigated in both the L1 and L2.

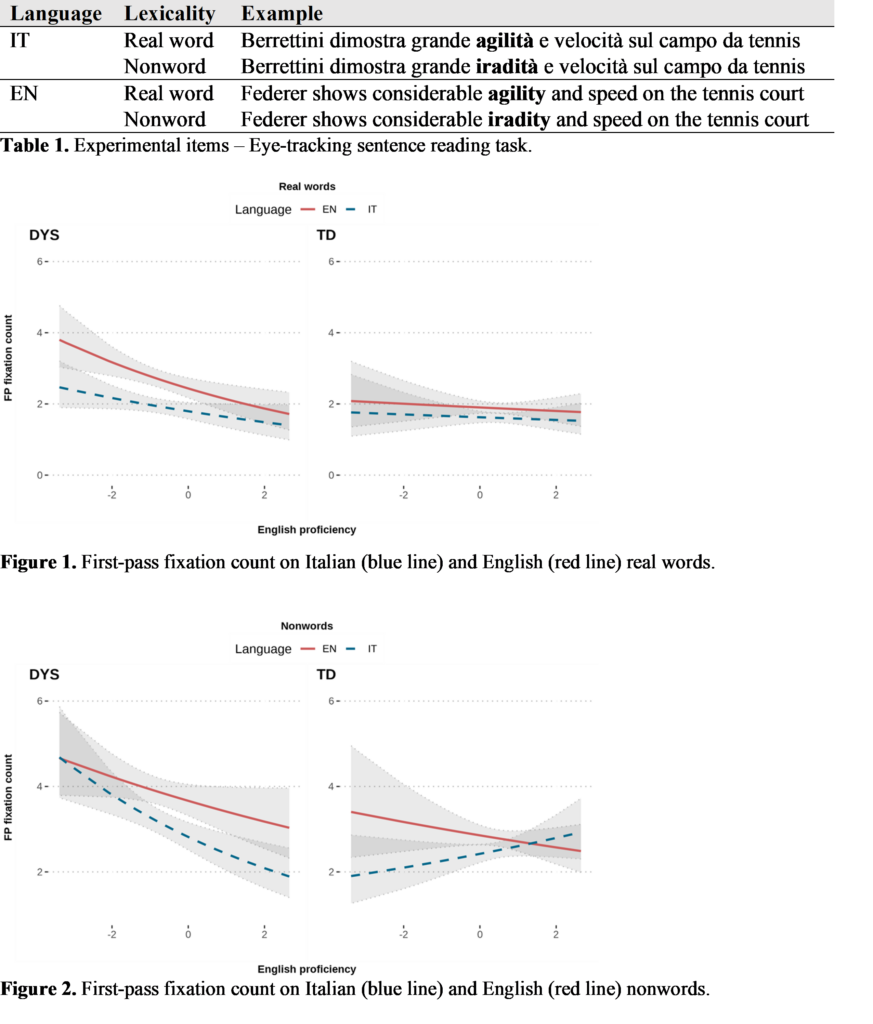

Method.Eighty participants took part in the study (M age = 17.05, SD = 1.43). Twenty-nine participants were formally diagnosed with DD. All participants were Italian native speakers and had started learning English at school (range = 3 – 8). An eye-tracking reading task was used to investigate whether identical words and nonwords are read differently when embedded in Italian vs. English sentences (Table 1).

Results. A glmer model analyzed fixation counts on target (non)words, considering Group (TD vs. DYS), Lexicality (Word vs. Nonwords), Language (IT vs. EN), and English proficiency. A significant four-way interaction (p = .027) indicated that English proficiency (marginally) significantly reduced fixations on Italian (p = .051) and English words (p = .002), and Italian (p < .001) and English nonwords (p = .058) in DYS participants. In TDs, English proficiency didn’t affect fixations in Italian (p = .702) or English words (p = .635), but its impact on Italian and English nonwords differed significantly (p = .046). Fixations decreased on English nonwords with increasing English proficiency. In contrast, fixations on Italian nonwords increased with English proficiency (Figure 1: real words, Figure 2: nonwords).

Discussion.Our findings indicate that improved proficiency in English reduces fixations on both Italian and English targets in DYS learners, regardless of lexicality, thus implying larger grain size unit processing as a function of higher English proficiency. Conversely, TDs show no English proficiency effects when reading Italian and English real words, arguably due to well-established lexical reading skills. Interestingly, increasing English proficiency in TDs correlates with more fixations on Italian nonwords, suggesting smaller grain size unit processing. This effect may support the hypothesis that highly proficient TDs are able to adapt their reading strategy to the target language [1]. Alternatively, it could suggest a strategy-switch cost. The implications of these results will be discussed.

Selected references:

- Ziegler, J. C., & Goswami, U. (2005). Reading Acquisition, Developmental Dyslexia, and Skilled Reading Across Languages: A Psycholinguistic Grain Size Theory. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 3–29.

- Lallier, M., & Carreiras, M. (2017). Cross-linguistic transfer in bilinguals reading in two alphabetic orthographies: The grain size accommodation hypothesis. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 25(1), 386–401.

- Egan, C., Oppenheim, G. M., Saville, C., Moll, K., & Jones, M. W. (2019). Bilinguals apply language-specific grain sizes during sentence reading. Cognition, 193.

Crosslinguistic influence can affect L1 feature representations: evidence from CLLD

Liz Smeets

York University, Toronto, Canada

A question in acquisition research is whether crosslinguistic influence exerted by the L2 ever affects L1 feature representations (i.e. grammatical attrition). Most studies on attrition of discourse properties have tested the Interface Hypothesis (IH), which argues that attrition affects only the ability to process interface structures, not knowledge representation (Sorace, 2011, Chamorro et al. 2016). We test attrition of a discourse property using the Attrition via Acquisition model (Hicks & Dominguez, 2020). Following Lardiere (2009) for L2 acquisition, the AvA argues that feature changes to the L1 grammar involve the addition of grammatical forms transferred from an analogous L2 structure.

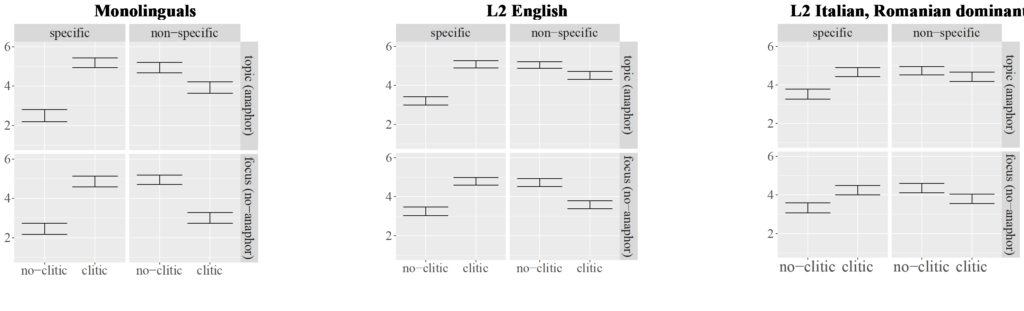

We examine the features associated with Clitic Left Dislocation in Romanian versus Italian, comparing two types of object left dislocation: contrastive topic and focus fronting. Italian and Romanian differ in the contexts in which they use clitics. In Romanian, both fronted topics [+anaphor] and fronted foci [-anaphor] require a clitic (compare 1b to 2b), but only when the left dislocated object is specific (compare 1b to 3b). The specificity distinction is irrelevant for Italian (compare 1a to 3a). In Italian, the insertion of a clitic after a dislocated direct object is restricted to contrastive topics and is disallowed with contrastive focus fronting (compare 1a to 2a). Thus, in Italian, CLLD is constrained by discourse anaphoricity (following López, 2009) and in Romanian by specificity.

Assuming that offline tasks reflect knowledge representation, we report on an acceptability judgment task presented in oral and written form where participants rated answers to questions (see (1)-(3)) and on a written elicitation task where participants had to complete missing verbs or clitics+verbs in sentences with object initial word orders (see example in (4)). Participants were 17 Romanian and 18 Italian monolinguals, Romanian immigrants to Italy (n=37) and to Canada/US (n=30), the latter being a control group to examine potential attrition not induced by the L2 grammar, as English does not use clitics.

Results confirm a discourse effect for Italian monolinguals and a specificity effect for Romanian monolinguals. Specificity was also the only significant factor for Romanians in Canada/US, while there was more variability for Romanians in Italy, suggesting influence from L2 Italian (see Fig. 1). Since attrition is typically categorized by individual variation, we further categorized the L2 Italian group based on their reported language dominance, defined as frequency of current language and self-reported language proficiency. We found a significant effect of both discourse and specificity for Romanians in Italy who were dominant in Italian (n=14). Like monolinguals and Romanian dominant speakers, they allowed clitics with fronting of both specific topics and foci, but also with non-specific topics, an option transferred from their L2.

Our findings support the AvA, as grammatical attrition was found for Romanians in Italy, resulting in the addition of the L2 option without loss of the L1 option. The results contribute to a better understanding of the factors that modulate attrition, showing it can cause a change in speakers’ L1 knowledge representation and does not only affect online sensitivity with interface structures.

| [+anaphor] (topic) | [-anaphor] focus | |||

| [+Specific] Condition 1 | [-Specific] Condition 2 | [+Specific] Condition 3 | [-Specific] Condition 4 | |

| English | ☓ | ☓ | ☓ | ☓ |

| Italian | ✓ | ✓ | ☓ | ☓ |

| Romanian | ✓ | ☓ | ✓ | ☓ |

Figure 1: Mean acceptability ratings (1-6) of Romanian monolinguals and Romanians in US/Canada and Italy. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Selected References:

- Chamorro, Sorace & Sturt. (2016). What is the source of L1 attrition? The effect of recent L1 re-exposure on Spanish speakers under L1 attrition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(3).

- Gürel, A. & Yılmaz, G. (2011). Restructuring in the L1 Turkish grammar: effects of L2 English and L2 Dutch. Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 2(2), 221-250.

- Hicks, G. and Domínguez, L. (2020). A model for L1 grammatical attrition. SLR, 36(2), 143–165.

- López, L. (2009). A derivational syntax for information structure. Oxford University Press.

Crosslinguistic influence in child bilingual acquisition: A Visual World eye-tracking study on grammatical case and aspect processing by German-Russian and Spanish-Russian bilinguals

Serge Minor, Natalia Mitrofanova

UiT – The Arctic University of Norway

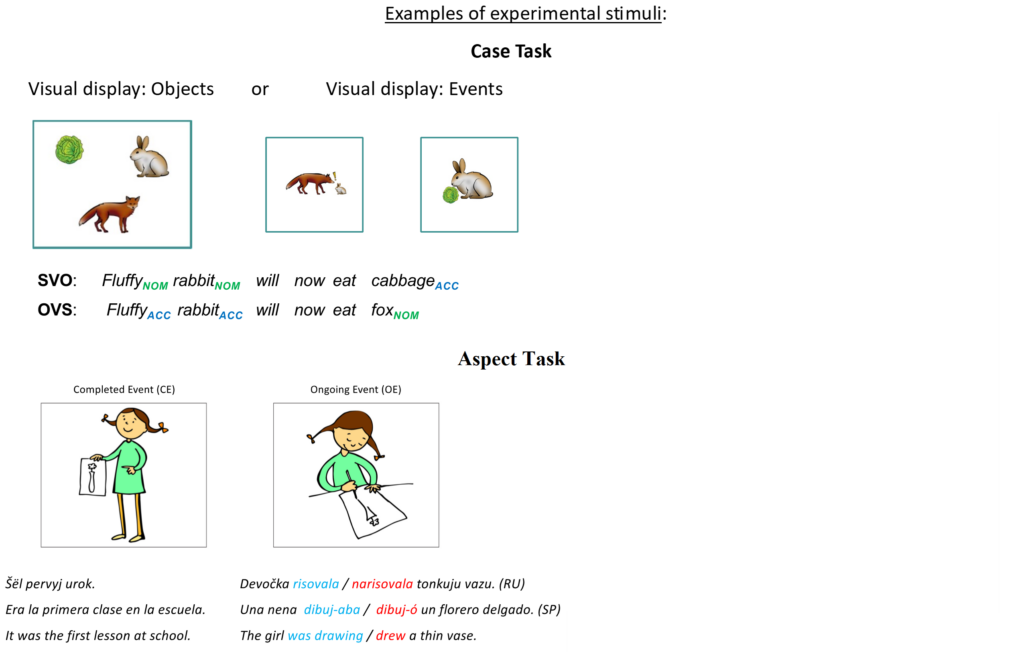

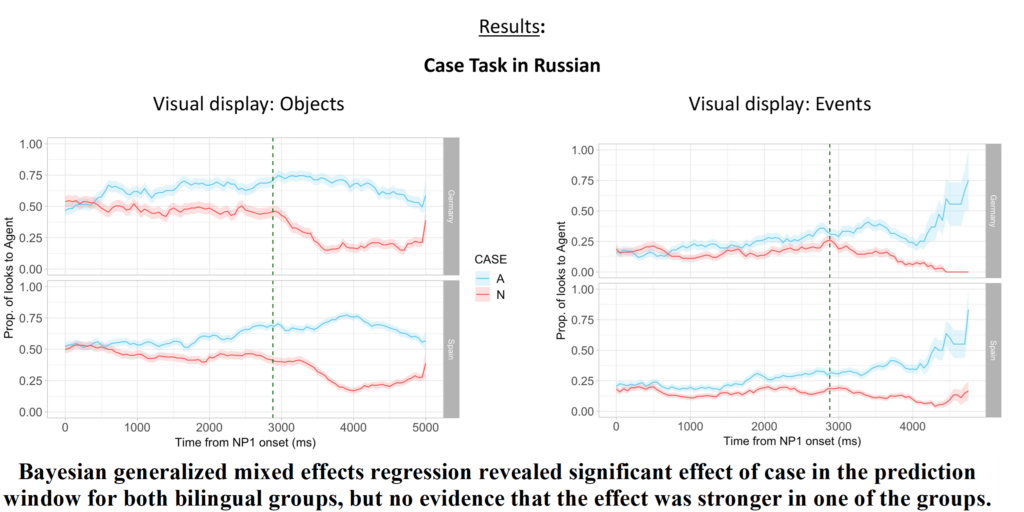

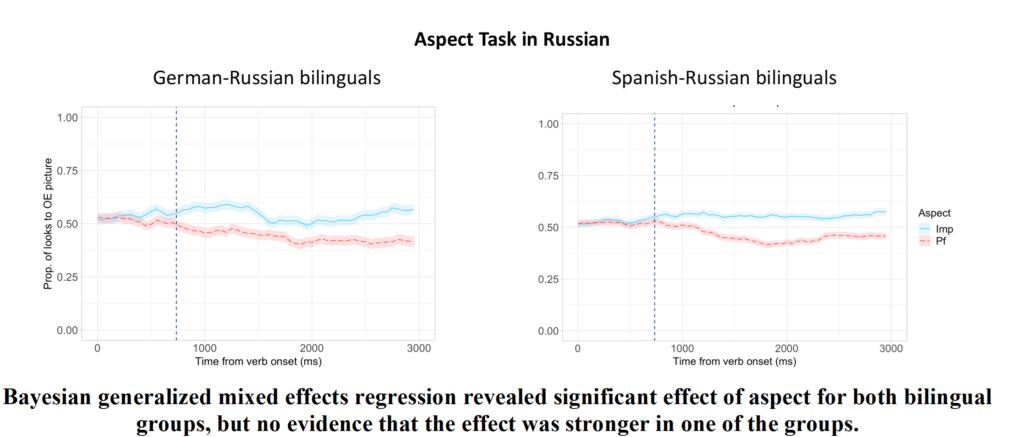

We investigate the effects of crosslinguistic influence (CLI) in grammatical processing by comparing across bilingual groups, carefully matched by background and lexical proficiency. We employ Visual World eyetracking and focus on the processing of grammatical case and aspect by Russian heritage 6-12 y.o. bilinguals. Both case and aspect have been found to be vulnerable in heritage Russian [1] and acquired early in monolinguals [2]. The heritage Russian speakers were sampled from two populations: Spanish-Russian (n= 85) and German-Russian bilinguals (n=45) closely matched by age, overall exposure (Q-Bex) and lexical proficiency in the heritage language (MAIN narratives). The choice of the populations was determined by structural similarity between languages: Russian and German both mark grammatical case (nominative vs accusative) in the noun phrase, while Spanish doesn’t employ overt case marking. On the other hand, Spanish and Russian exhibit a certain overlap in their use of verbal aspect (perfective vs imperfective) to distinguish between completed vs ongoing events in the past, while German doesn’t grammatically mark verbal aspect.

We used a paradigm based on [3] to investigate whether the participants could use nominative vs accusative case marking on the first NP to anticipate the possible continuation of the sentence, and a paradigm based on [4] to test whether the participants look at the picture representing an ongoing event more when they listen to a verb in the imperfective aspect vs perfective aspect. We present results on the processing of 1) grammatical case (in Russian: by two groups of bilinguals in comparison to each other as well as monolingual Russian-speaking children; and in German: by German-Russian bilinguals and monolingual German-speaking children) and 2) grammatical aspect (in Russian: by two groups of bilinguals in comparison to each other as well as monolingual Russian-speaking children, and Spanish: by Spanish-Russian bilinguals and monolingual Spanish-speaking children). We used Bayesian generalized mixed regression analysis to statistically evaluate the differences between the bilingual groups and the respective monolingual controls. The analysis revealed a significant effect of both case and aspect in Russian in the bilingual groups, with no differences between the bilingual groups on either case or aspect. Although no facilitation from the societal language was observed in the processing of case and aspect in the heritage language, our results indicate that there may be facilitation from the heritage language to the societal language for the bilingual participants. We discuss the results in light of further studies that report differential effects of CLI on the sociatal language vs the heritage language of bilingual children.

Selected references:

- Polinsky (2008). Without aspect. In Case and Grammatical Relations, OUP.

- Ceitlin (2000). Jazyk i rebjonok: Lingvistika detskoj recˇi. [Language and Child: Linguistics of Child Speech].

- Kamide et al. (2003). Integration of Syntactic and Semantic Information in Predictive Processing: Cross-Linguistic Evidence from German and English. J.of Psyling.R.

- Zhou et al. (2014). Grammatical aspect and event recognition in children’s online sentence comprehension. Cognition.

Cross-linguistic priming of relative clause comprehension in English-Dutch and German-Dutch bilingual children: Evidence for cumulative priming

Chantal van Dijk (Centre for Language Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen; Technische Universität Braunschweig; University of Stuttgart), Gerrit Jan Kootstra (Centre for Language Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen), Sharon Unsworth (Centre for Language Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen)

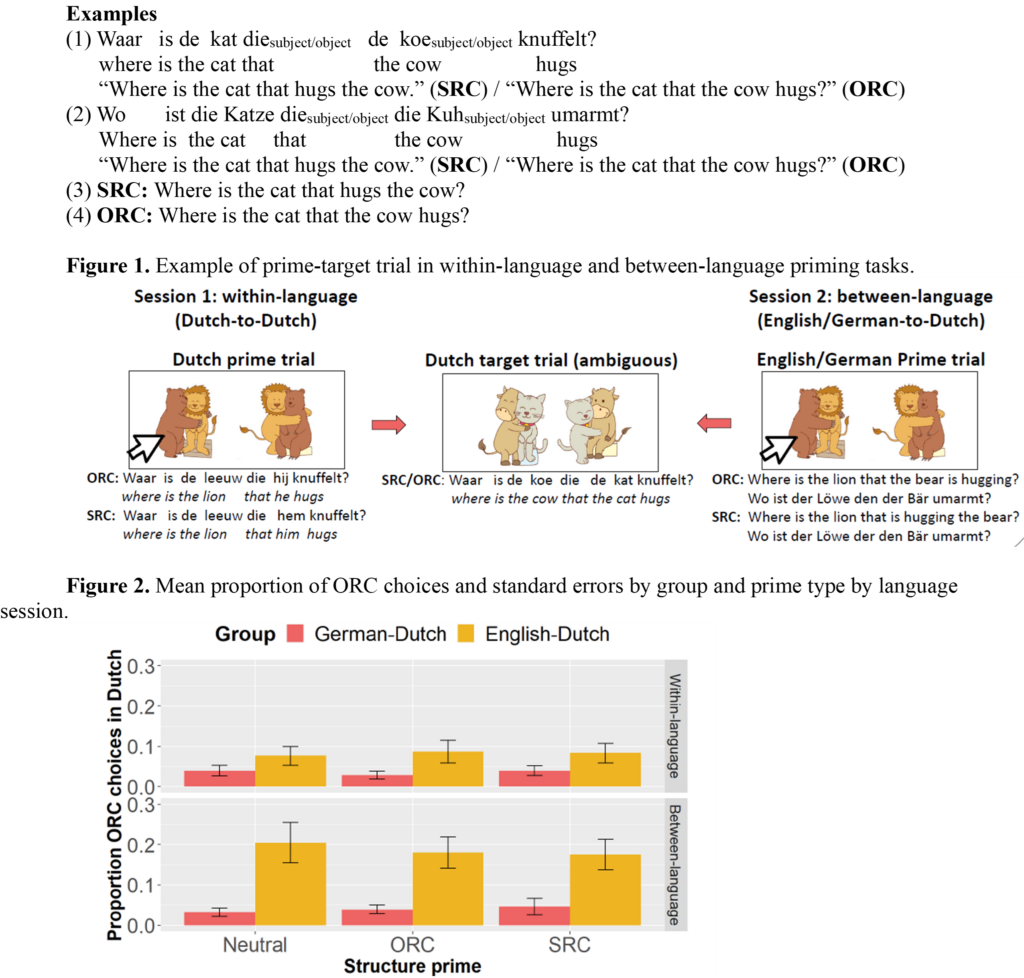

Cross-linguistic influence in bilingual acquisition has been conceptualised as cross-linguistic priming, that is, the result of long-term prior linguistic exposure (e.g., Serratrice, 2016). Whilst some evidence exists for cross-linguistic structural priming in children’s production (e.g., Unsworth, 2023; Vasilyeva et al., 2010), evidence for cross-linguistic priming in children’s comprehension is indirect only: through studies on cross-linguistic influence (e.g., Serratrice, 2007) and with adult L2 learners (e.g., Kidd et al., 2015). Consequently, it is unclear whether cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children’s is the outcome of cross-linguistic priming. Therefore, this study investigates bilingual children’s relative clause (RC) comprehension in within- and between-language priming tasks, asking the following questions:

(RQ1) Is there cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children’s RC comprehension?

(RQ2) Can we prime this cross-linguistic influence?

(RQ3) Are RC priming effects cumulative?

Thirty-six English-Dutch and 35 German-Dutch bilingual children (6-to-11 years) participated. RC word order in Dutch (1) and German (2) is ambiguous between a subject (SRC) and an object interpretation (ORC). English SRCs and ORCs word orders differ (3 and 4) with ORC order overlapping with Dutch and German RCs. Children were tested in two sessions (Figure 1). In session 1, they conducted a within-language priming task (Dutch-to-Dutch) that served as a baseline. Target items were spoken Dutch ambiguous RCs paired with two pictures: the SRC and ORC interpretation. Children chose the picture they believed matched the RC. Each target was preceded by a prime. Primes were similar to targets, except that they contained disambiguated SRCs or ORCs (i.e. by pronouns) or an unrelated sentence (e.g., “Where is the big cat?”). In session 2 (English-to-Dutch and German-to-Dutch), Dutch prime sentences were replaced by English or German primes. In English, RCs were disambiguated by word order, in German, by case marking. Children’s ORC choices were analysed. Furthermore, to investigate cumulative priming effects, we calculated children’s previous number of ORC choices for each trial.

Regarding RQ1, generalized linear mixed effect models showed significant main effects of group and session and a significant group-by-session interaction. English-Dutch children were more likely to interpret Dutch ambiguous RCs as ORCs than German-Dutch children and English-Dutch children’s ORC choices increased from in the between-language session (Figure 2). These effects suggest cross-linguistic influence from English to Dutch: English ORC-order overlap boosted the ORC interpretation for ambiguous RCs (e.g., Hulk & Müller, 2001). Regarding RQ2, there were no significant effects of or interactions with prime structure. Hence, there was no evidence of Dutch-to-Dutch, nor English/German-to-Dutch RC comprehension priming. Regarding RQ3, there was a positive relationship between English-Dutch children’s previous ORC choices and ORC choice on a given trial in both experiments. This finding suggests that whilst there were no direct priming effects visible in the English-Dutch group, their exposure to ORCs in both Dutch and English primed the ORC interpretation in Dutch over time.

Our findings offer evidence that cross-linguistic influence in bilingual acquisition is the outcome of long-term cross-linguistic priming, also in comprehension, in line with error-based learning (e.g., Chang et al., 2006).

References:

- Chang, F., Dell, G. S., & Bock, K. (2006). Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review, 113(2), 234–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033- 295X.113.2.234

- Kidd, E., Tennant, E., Nitschke, S. (2015). Shared abstract representation of linguistic structure in bilingual sentence comprehension. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 1062–1067. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0775-2

- Serratrice, L. (2007). Cross-linguistic influence in the interpretation of anaphoric and cataphoric pronouns in English–Italian bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728907003045

- Serratrice, L. (2016) Cross-linguistic influence, cross-linguistic priming and the nature of shared syntactic structures. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 6(6), 822-827. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.6.6.15ser

- Unsworth, S. (2023). Shared syntax and cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children: Evidence from between- and within-language priming. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.22093.uns

- Vasilyeva, M., Waterfall, H., Gamez, P. B., Gomez, L. E., Bowers, E., & Shimpi, P. (2010). Cross-linguistic syntactic priming in bilingual children. Journal of Child Language, 37(5), 1047.

How bilingualism influences language processing in the developing brain: A systematic review of the neurobiological evidence

Chih Yeh1,3, Caroline F. Rowland1,2, Sergio Miguel Pereira Soares1

1Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 3Max Planck School of Cognition, Leipzig, Germany

Sergio-Miguel.Pereira-Soares@mpi.nl

Previous literature has revealed that bilingual experiences influence language processing, development and induce neurobiological changes. Work so far has focused on several aspects (e.g., phonetic contrasts discrimination, vocabulary growth, and word learning) and probed similar research questions using different methods. Crucially, no study has yet attempted to understand how these findings fit together, and whether they report comparable or conflicting findings. Therefore, a systematic understanding of neural correlates in the developing bilingual brain is needed. Herein, we review emerging findings on the developing bilingual brain from 98 peer-reviewed studies across methodologies (online processing: MEG/EEG/ERP; neuronal activity: fNIRS/fMRI, structural changes: MRI/DTI), ages, and languages to provide a more holistic understanding for the entire literature. These studies contain different types of bilinguals: simultaneous bilingual, sequential bilingual, and L2 learner.

The literature on simultaneous bilingual acquisition focuses primarily on comparing first language acquisition between bilinguals and monolinguals. Findings suggest that simultaneous bilinguals tend to exhibit greater and long-lasting neural and behavioral sensitivity to phonetic contrasts compared to monolinguals. However, it suggests that simultaneous bilinguals also require more time to acquire the phoneme inventories for both languages due to less exposure than their monolingual peers. Despite similar behavioral performances in various tasks, simultaneous bilinguals show different brain responses from monolinguals, requiring more bilateral and DLPFC activation, more attentional control for language processing, and greater reliance on pragmatic cues in context. Other studies compare neurobiological differences between simultaneous bilinguals, sequential bilinguals, and monolinguals. Results show that sequential bilinguals often fall between the other two groups. For instance, sequential bilinguals tend to have higher cortical thickness compared to simultaneous bilinguals but lower compared to monolinguals; or they have less refined white matter tracts within language-related areas compared to simultaneous bilinguals, but better than monolinguals.

The literature investigating L2 learners focuses more on individual differences. Many studies show prominent relations between L2 proficiency and the corresponding neurobiological changes. L2 learning in childhood follows similar developmental trajectories to L1 acquisition, i.e., native-like ERP patterns in language processing, greater activation from language areas, and a gradual shift from bilateral to left-lateralized brain responses as L2 proficiency increases. Eventually, the L2’s brain networks converge to those of the L1.

Finally, we integrated the developmental literature with two bilingual frameworks based on adult studies—Adaptive Control Hypothesis (ACH) and Dynamic Restructuring Model (DRM). Results for simultaneous bilinguals align with the ACH, suggesting that bilingual processing imposes greater cognitive demands. Therefore, a reconfiguration of neural networks to optimize language performance in bilingual brains is often observed. Some other findings speak rather in favor of the DRM, by focusing on the interaction between the amount of language exposure, proficiency, and neuroadaptation. Indeed, with increasing bilingual experience, bilingual children appear to exhibit comparable brain responses and structural changes as described in DRM. In sum, although several patterns emerged, further research is required to advance our understanding of the effects of bilingual language acquisition in the developing brain.

Linking offline judgements and ERP responses in the L1 and L2 processing of filler-gap dependencies

Ioannis Iliopoulos, Claudia Felser

Potsdam Research Institute for Multilingualism (PRIM)

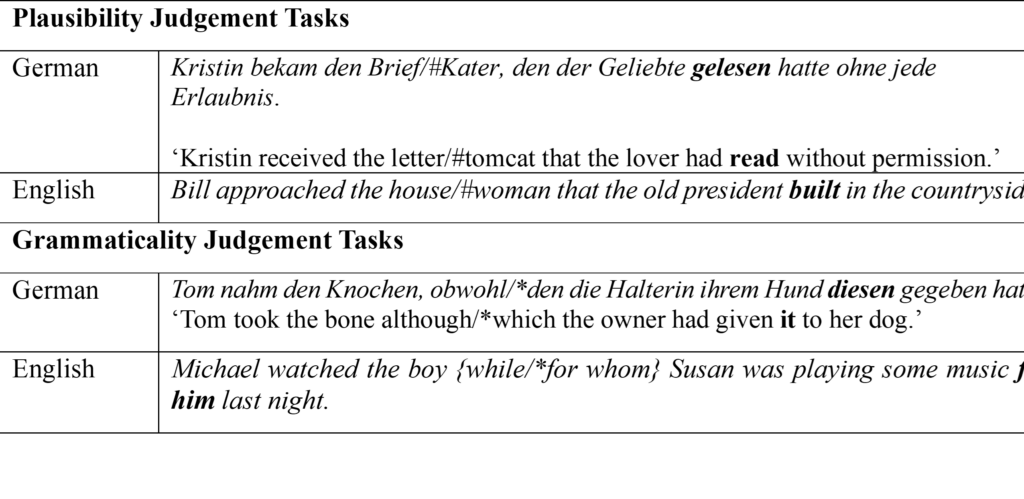

The degree to which second language (L2) learners can acquire implicit (vs. explicit) knowledge of the target language has been subject to much debate. While offline judgments are commonly used as metrics for explicit knowledge, event-related potentials (ERP) have been taken to be indicators of implicit sensitivity to the L2 property under investigation (e.g. Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005). Exploration of the relationship between offline judgments and ERPs has thus far been confined to the P600 ERP component (Lemhöfer et al., 2014; Morgan-Short et al., 2022; White et al., 2012). The present study contributes to this line of research by investigating the relationship between the brain responses elicited by ill-formed filler-gapdependencies and end-of-trial judgements. We innovate on previous work by testing the same individuals in both their native language (L1) and their L2, and by examining their sensitivity to both grammatical and semantic anomalies across structurally similar sentences.

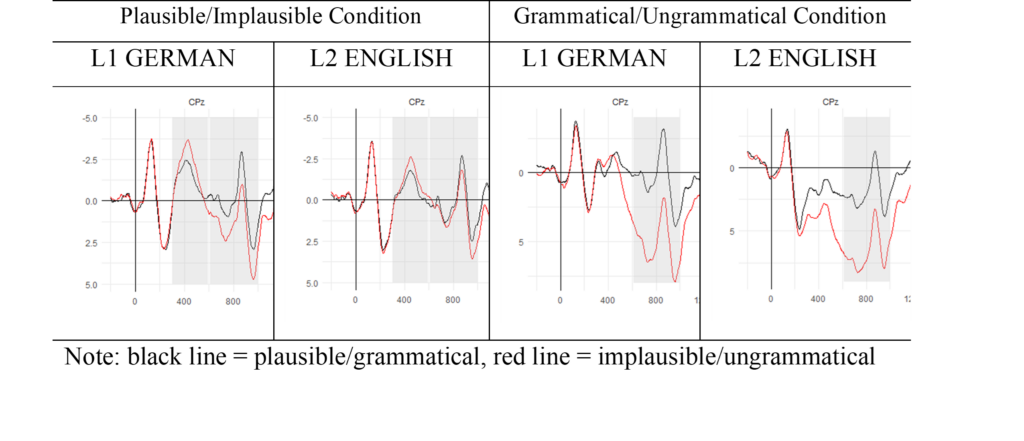

106 L1 German/L2 English speakers (Age: 25.53 years [sd: 5.5]; AoA: 8.2 years [sd: 2.07]; L2 proficiency: CERF level C1 [range: B1-C2]) took part in two (one in German, one in English) binary plausibility and two binary grammaticality judgement tasks while their brain responses were being recorded. Our stimulus sentences involved extraction from relative clauses with either semantically plausible vs. implausible fillers, or with a filled vs. unfilled gap position (Table 1). The plausibility and grammaticality judgement data were analysed separately. Mixed-effects models showed significant interactions with Language, reflecting larger Plausibility and Grammaticality effects in participants’ L1 than in their L2. An initial analysis of the EEG recordings revealed a bi-phasic N400/P600 effect for the plausibility manipulation and a P600 effect for the grammaticality manipulation (Figure 1). The aggregated amplitudes of a central ROI (C1, C2,C3,C4,Cz) for the N400 and a posterior ROI (P1, P2, P3, P4, Pz) for the P600 effects were later inserted as dependent variables into three linear mixed-effects models, with Language, Judgement and Plausibility/Grammaticality as independent variables. Results showed that the size of the N400 response was solely modulated by Plausibility, with no effect of, or interaction with, the factor Judgement. For the P600 triggered by the same stimuli, we found a significant interaction of Judgement and Plausibility, with an increased P600 response for implausible sentences that were correctly rejected. The same interaction pattern was attested for the P600 data in the grammaticality judgement task, with a larger P600 response for filled-gap sentences that were correctly rejected. No significant interactions with the factor Language were observed.

Summarising, although participants’ offline judgements were less accurate overall in their L2 than in their L1, we observed similar ERP patterns to semantic (N400 & P600) and syntactic (P600) anomalies in both languages. Independently of language status, P600 responses were larger for accurate judgements, whereas the size of the N400 response to implausible stimuli was unrelated to judgement accuracy. These findings support and extend previous findings linking the P600 to explicit knowledge (e.g. Morgan-Short et al., 2022), while suggesting that the N400 response may be associated with implicit processing.

Table 1: Example stimulus sentences for plausibility and grammaticality judgement tasks in German and English

Figure 1: Average ERP waves at the CPz electrode in L1 and L2 at the words marked in bold in Table 1.

References:

- Lemhöfer, K., Schriefers, H., & Indefrey, P (2014). Idiosyncratic grammars: Syntactic processing in second language comprehension uses subjective feature representations. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26, 1428–1444.

- Morgan-Short, K., Finestrat, I., Luque, A., & Abugaber, D. (2022). Exploring new insights into explicit and implicit second language processing: Event-related potentials analyzed by source attribution. Language Learning, 72, 365–411.

- Tokowicz, N., & MacWhinney, B. (2005). Implicit and explicit measures of sensitivity to violations in second language grammar: An event-related potential investigation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, 173–204.

- White, E. J., Genesee, F., & Steinhauer, K. (2012). Brain responses before and after intensive second language learning: Proficiency based changes and first language background effects in adult learners. PLoS ONE, 7(12), 1–18.

Network science tools unveil the early stages of L1 lexical attrition

Adel Chaouch-Orozco,

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

adel.chaouchorozco@polyu.edu.hk

L1 lexical attrition, the weakening or loss of L1 lexical-semantic abilities, is attributed to reduced L1 exposure and/or L2 interference (Schmid et al., 2019). Semantic fluency tasks, where participants provide exemplars of a given semantic category within a timeframe, are central to L1 attrition research. However, traditional analyses have yielded inconclusive results (Schmid & Köpke, 2009). While some studies indicate that L1 attriters name fewer items than functional monolinguals, others report no significant differences (Jarvis, 2019). Our study moves beyond traditional analyses, employing a novel network science approach to investigate the bilingual lexicon’s structural properties, thus offering a fresh perspective in L1 attrition research.

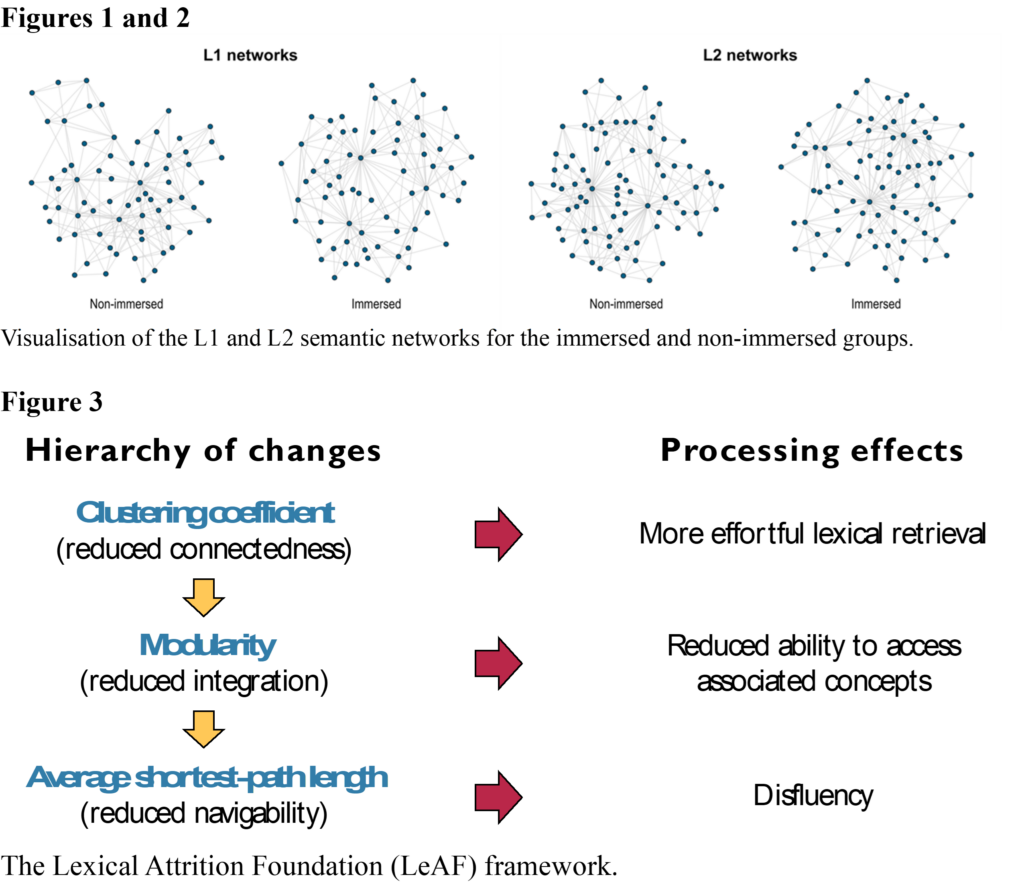

Data from two semantic fluency tasks were collected from 94 immersed and 80 non-immersed late bilinguals with comparable L2 proficiency (as measured by the OQPT). In their L1 Spanish, participants provided exemplars of the fruits and vegetables category, whereas in L2 English, they named animals. Following previous studies (Christensen & Kenett, 2021), we built networks with nodes representing words and edges capturing co-occurrences. The analysis focused on three network measures reflecting the lexicon’s structural organisation, which may be critically impacted during lexical attrition (Gallo et al., 2021): Clustering coefficient (CC), the degree to which nodes group together; average shortest-path length (ASPL), the average distance between node pairs; and modularity (Q), the degree to which the network comprises distinct communities. Importantly, higher CC is associated with better semantic organisation in bilinguals and monolinguals (Cosgrove et al., 2021; Feng & Liu, 2023); lower ASPL with faster navigability within the lexicon (Siew & Guru, 2023); and lower Q with more efficiently organised knowledge networks (Siew & Guru, 2023).

We examined if L2 immersion results in L1 lexical attrition, manifested by shifts in the native semantic system’s structure, reflected by lower CC, higher ASPL, and Q. Bootstrap analyses were conducted, involving the generation of partial networks from randomly selected node subsets, repeated 1000 times for subsets containing 50% to 90% of the original network nodes. This created a sampling distribution for each measure and network. Using analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), we found significant differences between the L1/L2 semantic networks of immersed and non-immersed bilinguals. The L1 networks of the immersed participants showed signs of attrition, being less densely connected and sparser (Figure 1). Conversely, their L2 networks displayed a more efficient organisation than those of the non-immersed subjects (Figure 2). In-depth analyses examining language use and proficiency further validated these observations. Notably, these trends were not observed in traditional analyses like response count.

These findings demonstrate the network science approach’s effectiveness in elucidating the complex dynamics of bilingual semantic memory systems. Furthermore, our analysis indicated that the erosion of the native semantic system is a gradual process, first impacting network interconnectivity, with information flow and community structure being less affected initially. Drawing from these insights, we introduce the Lexical Attrition Foundation (LeAF) framework, offering a network-based developmental perspective on lexical attrition and laying the groundwork for future research (Figure 3).

References:

- Christensen, A. P., & Kenett, Y. N. (2021). Semantic network analysis (SemNA): A tutorial on preprocessing, estimating, and analyzing semantic networks. Psychological Methods, 28(4), 860-879.

- Cosgrove, A. L., Kenett, Y. N., Beaty, R. E., & Diaz, M. T. (2021). Quantifying flexibility in thought: The resiliency of semantic networks differs across the lifespan. Cognition, 211, 104631.

- Feng, X., & Liu, J. (2023). The developmental trajectories of L2 lexical-semantic networks. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1-12.

- Jarvis, S. (2019). Lexical attrition. In M. S. Schmid and B. Köpke (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Language Attrition (pp. 241–50). Oxford University Press.

- Schmid, M. S., & Köpke, B. (2009). L1 attrition and the mental lexicon. In A. Pavlenko (Ed.), The bilingual mental lexicon: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 209-238). Multilingual Matters.

- Schmid, M. E., Köpke, B. E., Cherciov, M. C., Karayayla, T. C., Keijzer, M. C., De Leeuw, E. C., et al. (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Language Attrition. Oxford University Press.

- Siew, C. S., & Guru, A. (2023). Investigating the network structure of domain-specific knowledge using the semantic fluency task. Memory & Cognition, 51(3), 623-646.

- Siew, C. S., Wulff, D. U., Beckage, N. M., & Kenett, Y. N. (2019). Cognitive network science: A review of research on cognition through the lens of network representations, processes, and dynamics. Complexity, 2019.

Phonological effects in predictive processing of syntax: eye-tracking evidence from L1 Mandarin speakers in the UK

James Turner (University of Southampton),

Lewis Baker (Technische Universität Braunschweig)

lewis.baker@tu-braunschweig.de

Whilst a considerable number of studies have investigated the role of semantics in bilinguals’ predictive processing of syntax (e.g., several studies demonstrate that bilinguals’ greater reliance on lexical semantics compared to morphosyntax leads to quantitative and qualitative differences in bilingual vs. monolingual processing), far less attention has been given to cases where bilinguals’ phonological processing may likewise influence their predictive processing of syntax (see Schlenter, 2023 for a recent review of predictive processing studies with bilinguals).

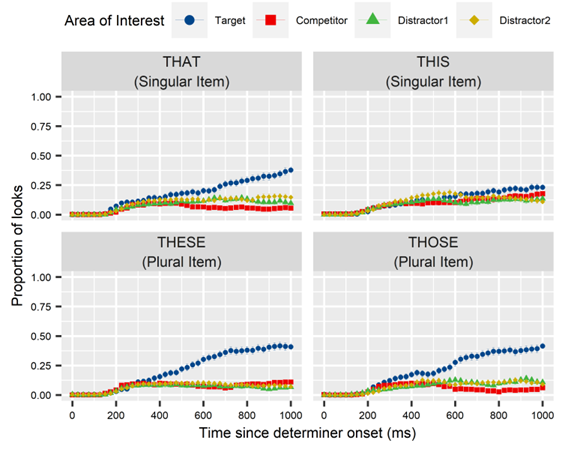

We tested 30 L1 Mandarin speakers who had just begun a residence abroad at a UK University along with 30 L1 English controls. All participants completed two Visual World eye-tracking experiments testing syntactic and phonological processing in English. The syntax experiment tested predictive processing of number with the determiners this/these/that/those, each followed by a balanced number of singular and plural nouns, as well as the+noun to test sensitivity to nominal number marking independent of determiner number marking (English and Mandarin differ regarding number morphology). The phonology experiment tested processing of minimal pairs contrasting /i/ vs. /ɪ/ (e.g., sheep vs. ship), a tense-lax contrast which is known to be difficult for L1 Mandarin learners of English (Yang et al., 2016), as well as minimal pairs contrasting word-final /z/ vs. /s/ (e.g., rise vs. rice). Given that the /i/–/ɪ/ contrast helps to distinguish the English determiners these and this (along with /z/–/s/), we hypothesised that participants who struggle with the processing of these vowels would also struggle to use these two determiners predictively in online processing.

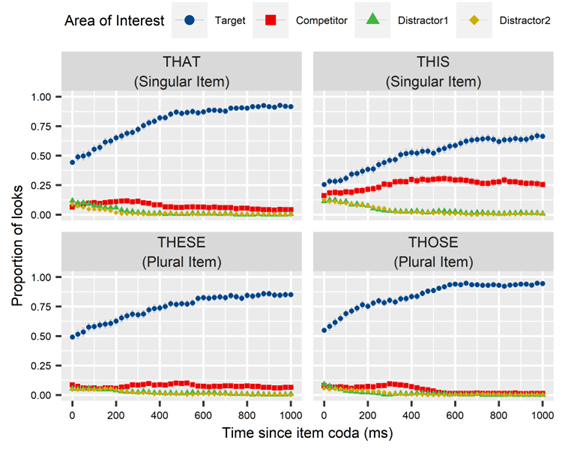

Results of the syntax experiment reveal that for the congruent conditions (e.g., that + singular noun), L1 Mandarin speakers correctly predict the upcoming noun. The exception is the determiner this (see Figure 1). Mixed effects binomial logistic regression modelling confirms that the difference between the proportion of looks to the target and competitor is significantly lower for the this condition compared to the other determiners. Further analyses suggest this may be linked to a phonological processing difficulty: in the phonology experiment, the difference between the proportion of looks to target and competitor increases significantly more slowly for /ɪ/ over time than for /i/ (i.e., the L1 Mandarin speakers find the processing of the vowel in this more challenging than the vowel in these). This is likely due to the phonetics of the Mandarin /i/ vowel mapping on to English /i/ more straightforwardly than English /ɪ/. In the incongruent conditions of the syntax study, L2 learners are able to retreat from their initial predictions from the determiner when they encounter the noun coda (i.e., the point at which they hear nominal plural morphology/lack thereof), similarly to the native controls. However, unlike the controls, in the congruent this + singular noun condition it appears that the L1 Mandarin speakers never fully discount the plural noun (Figure 2) even after processing the nominal coda. This is again confirmed by statistical modelling and possible explanations are explored.

Figure 1: Determiner onset

Figure 2: Noun Coda

References:

- Schlenter J. (2023). Prediction in bilingual sentence processing: How prediction differs in a later learned language from a first language. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 26(2), 253-267. doi: 10.1017/S1366728922000736

- Yang, X., Shi, F., Liu, X. & Zhao, Y. (2016). Learning styles and perceptual patterns for English /i/ and /ɪ/ among Chinese college students. Applied Psycholinguistics, 37. doi: 10.1017/S014271641500020X

The effects of changing the word order of collocations on L2 sentence processing: an eye-tracking study

Wanyin Li (University of Birmingham),

Bene Bassetti (University of Modena and Reggio Emilia;

University of Birmingham), Steven Frisson (University of Birmingham)

Research show collocations (defined as pairs of words that occur together frequently) are processed faster than free word combinations in both L1 and L2 readers (e.g., Vilkaitė & Schmitt, 2019; Vilkaitė, 2016). This faster processing of collocations compared with novel word combinations is called the ‘collocation advantage’. The advantage is mainly observed for canonical collocations (where collocations occur in their default configurations, e.g., provide information); however, in natural language, collocations also occur in non-canonical/non-default configurations. For L1 readers, the collocation advantage was still observed for two types of variations: non-adjacency (where one or more words are inserted between the components of a collocation .e.g. provide some of the information)(Vilkaitė, 2016), and morphological variation (where the morphological forms of the words are modified, e.g., provides/providing information (Vilkaitė-Lozdienė, 2022). In contrast, for L2 readers, one study found that the processing advantage disappeared in non-adjacent collocations (Vilkaitė & Schmitt 2019). This result may indicate that L2 readers process non-canonical collocations differently from L1 readers. However, other types of variation collocations have not been investigated in L2 speakers.

The present eye-tracking reading experiment investigated whether collocations with a modified word order, specifically passivized collocations, still show an advantage (e.g., active collocation: he improved quality -> passive collocation: quality was improved), whether word order changes affect L1 and L2 readers similarly, and whether the collocation advantage is separate from contextual predictability. Thirty-nine advanced L2-English learners and 40 English natives read 48 sentences containing either an active collocation, a passive collocation, or their corresponding controls (counterbalanced). Example: …he improved/discussed quality… (active), …quality was improved/discussed… (passive).

Generalised mixed models revealed that changing the word order of collocations did not eliminate the collocation advantage in either L1 or L2 readers. The collocation advantage was still present, even with contextual predictability strictly controlled, but it was more consistent in late rather than early reading measures. This study provides evidence that advanced L2 readers process non-canonical collocations with modified word order in a qualitatively similar manner to L1 readers, and that the impact of variation on the processing of collocations might depend on the type of modification (cf. Vilkaitė & Schmitt, 2019) and/or to what degree variation collocations are different from their canonical forms. In summary, our results do not support the view that L2 readers rely on rules and words while L1 readers match meaning to form (Wray, 2008). Rather, both L1 and L2 readers seem to adopt a more unified approach in collocation processing.

References:

- Vilkaitė-Lozdienė, L. (2022). Do different morphological forms of collocations show comparable processing facilitation? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1037/XLM0001130

- Vilkaitė, L., & Schmitt, N. (2019). Reading collocations in an L2:Do collocation processing benefits extend to non-adjacent collocations? Applied Linguistics, 40(2), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx030

- Vilkaitė, L. (2016). Are nonadjacent collocations processed faster? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 42(10), 1632–1642. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000259

- Wray, A. (2008). Formulaic language: Pushing the boundaries. Oxford University Press.

The impact of bilingual language proficiency on automatic speech recognition accuracy in children

Trisha Thomas 12, Andrea Takahesu-Tabori3, Antje Stoehr2, Ying Xu1

1 University of Michigan, Michigan, USA

2 Basque Center on Cognition, Brain and Language, San Sebastian, Spain

3 MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, USA

Recent advances in Automated Speech Recognition (ASR) and Generative Artificial Intelligence have led to a surge of voice-enabled applications, many of which are targeting child users such as educational apps, social robots, smart toys, and intelligent tutoring systems (Dousay et al., 2018). For young learners who are still developing their literacy proficiency and fine motor skills, ASR has the potential to lower interaction barriers and make digital content more accessible to them in service of their learning and development (Xu & Warschauer, 2020; Xu et al., 2021). However, these systems may be biased against speakers of diverse languages and dialects, which may exacerbate educational inequality (Koenecke et al., 2020). The United States is home to a diverse background of English speakers, with the largest group being Latinos growing up speaking Spanish. As educational tools incorporating ASR are implemented at increasingly larger scales, biases inherent in ASR may hinder their learning and thus exacerbate educational inequalities.

The present study examines the effect of language proficiency, assessed through the Bilingual English Spanish Oral Screener, of Spanish-English bilingual children from Southern California (N = 199; ages 3-7 years) on the transcription accuracy of their English speech by four widely used ASR systems (Amazon, Google, IBM, Whisper). Speech samples were sentence and word-level speech collected via a picture-naming task in English. Items consisted of a total of 30 monosyllabic, plosive-initial words that had been selected from the MacArthur Communicative Developmental Inventory (CDI) (Fenson et al., 2006) to ensure that the items being used were in the expressive vocabulary of the age group of our participants. The items consisted of 10 tokens of each of our phonemes of interest—the English voiceless plosives /p/, /t/ and /k/. We computed the phonetic distance (Aline) between ASR transcription and human transcription. We also measured voice onset time production, which is an acoustic feature that likely differs between bilingual and monolingual children (Fabiano-Smith & Bunta, 2012). 3 additional items were short, expressive sentences taken from the CDI that children were asked to repeat to analyze the Word Error Rates.

Analyses reveal differences in the accuracy of transcription between ASR systems and overall lower accuracies than reported in prior studies of ASR performance of monolingual English-speaking children (Sobti et al., 2024). Additionally, children who were older or more proficient in English had their speech transcribed more accurately by all APIs. We further investigated if the acoustic properties (VOT) of the children’s speech affected transcription accuracy but only found an effect of VOT on the ASR of IBM. While previous research has identified racial disparities in ASR among adult speakers, our study is the first rigorous study that directly focuses on ASR performance among Latino bilingual children. Because previous studies of adult speakers have found evidence for a lack of inclusivity in the acoustic models of ASR, bilingual children are at an increased risk of avoiding benefiting from educational advancements that rely on ASR. These results highlight the need for greater language diversity in ASR model development. We aim for insights gained from this research to help inform strategies for future inclusive technology development.

References:

- Dousay, T. A., & Hall, C. (2018). Alexa, tell me about using a virtual assistant in the classroom. EdMedia+ Innovate Learning, 1413–1419.

- Fenson, Larry, et al. (2006) “MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories, Second edition.” PsycTESTS Dataset, https://doi.org/10.1037/t11538-000.

- Koenecke, A., Nam, A., Lake, E., Nudell, J., Quartey, M., Mengesha, Z., Toups, C., Rickford, J. R., Jurafsky, D., & Goel, S. (2020). Racial disparities in automated speech recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(14), 7684–7689.

- Sobti, R., Guleria, K., & Kadyan, V. (2024). Comprehensive literature review on children automatic speech recognition system, acoustic linguistic mismatch approaches and challenges. Multimedia Tools and Applications.

- Xu, Y., Aubele, J., Vigil, V., Bustamante, A.S., Kim, Y.K., & Warschauer, M. (2021). Dialogue with a conversational agent promotes children’s story comprehension via enhanced engagement. Child Development.

- Xu, Y., & Warschauer, M. (2020b). Wonder with elinor: designing a socially contingent video viewing experience. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference: Extended Abstracts, 251–255.

The relationship between bilingual engagement and cognition across the adult lifespan in regional minority language contexts in the north of the Netherlands

Floor van den Berg, Raoul Buurke, Jelle Brouwer, Hanneke Loerts, Remco Knooihuizen, Martijn Bartelds, Martijn Wieling, and Merel Keijzer

Center for Language and Cognition Groningen, University of Groningen

The sustained and complex life experience of bilingualism has been previously linked to better-preserved cognitive functioning in the face of typical or pathological brain aging (Dash et al., 2022; Gallo et al., 2022). This cross-sectional study contributed to this line of work by investigating the association between a continuous measurement of bilingual engagement and cognitive aging in regional minority language contexts, which have received limited attention in the literature despite being quite common. We used an existing sample drawn from the Lifelines Cohort Study (Buurke et al., 2023; Scholtens et al., 2015; Sijtsma et al., 2022) comprising Frisian-Dutch bilinguals (n = 7,448) and Low Saxon-Dutch bilinguals (n = 10,114). All participants lived in the north of the Netherlands and ages ranged between 20 and 80, enabling an adult lifespan perspective. Cognitive functioning was measured using the Cogstate Brief Battery, which consists of four tasks assessing processing speed, attention, working memory, and recognition memory (Fredrickson et al., 2010). Bilingual engagement was operationalized as language entropy, calculated using the proportion of use of the regional minority language and Dutch across several conversational contexts (Gullifer & Titone, 2020). We modeled the relationship between age and bilingual engagement as a non-linear interaction using generalized additive mixed modeling and controlled for gender, educational attainment, and location-related variability in the analysis. The results demonstrated that performance on all cognitive tasks significantly decreased with age, but we did not identify a robust main effect of bilingual engagement or an interaction between bilingual engagement and age. As such, our results suggest that bilingual engagement does not play a key role in processing speed, attention, working memory, and recognition memory performance across the adult lifespan in Frisian-Dutch and Low Saxon-Dutch bilinguals. Implications for the bilingual engagement measurement and potential investigations into regional minority language bilingualism and cognition will be discussed.

References:

- Buurke, R., Bartelds, M., Knooihuizen, R., & Wieling, M. (2023). Examining maintenance and shift in regional language populations: The case of Frisian and Low Saxon in the Netherlands. Linguistic Minorities in Europe Online [submitted].

- Dash, T., Joanette, Y., & Ansaldo, A. I. (2022). Multifactorial approaches to study bilingualism in the aging population: Past, present, future. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 917959. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.917959

- Fredrickson, J., Maruff, P., Woodward, M., Moore, L., Fredrickson, A., Sach, J., & Darby, D. (2010). Evaluation of the usability of a brief computerized cognitive screening test in older people for epidemiological studies. Neuroepidemiology, 34(2), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1159/000264823

- Gallo, F., DeLuca, V., Prystauka, Y., Voits, T., Rothman, J., & Abutalebi, J. (2022). Bilingualism and aging: Implications for (delaying) neurocognitive decline. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, Article 819105. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnhum.2022.819105

- Gullifer, J. W., & Titone, D. (2020). Characterizing the social diversity of bilingualism using language entropy. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23(2), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728919000026

- Scholtens, S., Smidt, N., Swertz, M. A., Bakker, S. J. L., Dotinga, A., Vonk, J. M., van Dijk, F., van Zon, S. K. R., Wijmenga, C., Wolffenbuttel, B. H. R., & Stolk, R. P. (2015). Cohort Profile: LifeLines, a three-generation cohort study and biobank. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(4), 1172–1180. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu229

- Sijtsma, A., Rienks, J., van der Harst, P., Navis, G., Rosmalen, J. G. M., & Dotinga, A. (2022). Cohort Profile Update: Lifelines, a three-generation cohort study and biobank. International Journal of Epidemiology, 51(5), e295–e302. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab257

Whether prediction and adaptation lead to learning among beginning L2 learners

Carrie N. Jackson (Penn State University), Theres Grüter (University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa)

Some argue that structural priming and adaptation rely on implicit learning mechanisms, involving adjustment to linguistic representations due to prediction error (e.g., Chang et al., 2006). Building on this account, recent studies have shown that when L2 learners are explicitly forced to predict the structure of an upcoming (prime) sentence, they are more likely to experience prediction error and consequently exhibit greater adaptation, compared to simply copying a prime sentence (Grüter et al., 2021; see also Alzharani, 2023). However, these studies have investigated prediction and priming among intermediate or advanced L2 learners. Considering research that shows only participants with sufficient baseline knowledge of a target structure exhibit significant priming of that structure (Jackson & Ruf, 2017; McDonough & Fulga, 2015), it remains an open question whether this advantage for prediction-supported priming extends to beginning-level learners, who may not yet possess stable L2 linguistic representations.

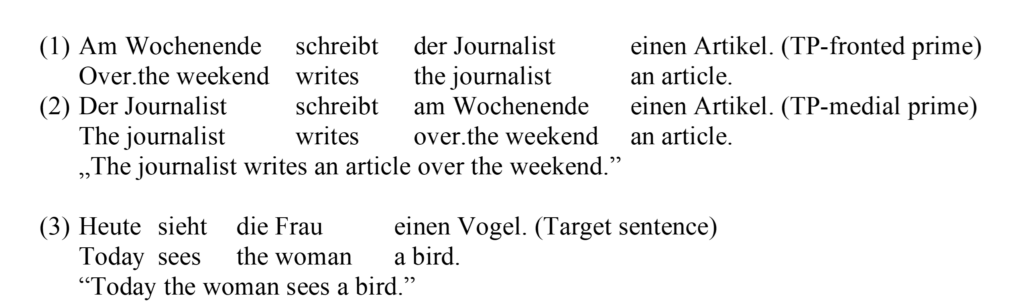

To address this question, beginning-level American L2 learners of German (n=33, ongoing) completed a written production priming experiment, focusing on adverb placement in L2 German. Prime sentences contained either a fronted temporal phrase (TP) or sentence-medial TP, as in (1) and (2). Both word orders are dispreferred in English and beginning-level L2 German learners are less likely to produce either word order, relying instead on S-V-O-TP word order, the preferred word order in their L1 English (Hopp et al., 2018; Jackson & Ruf, 2017).

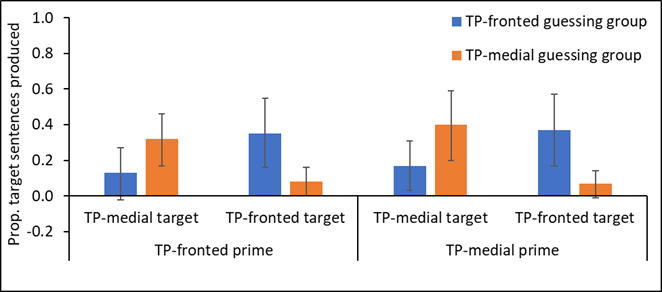

Using a within-subjects design, participants received either TP-fronted or TP-medial primes in a “guessing” condition, where they guessed how a virtual partner would describe a picture prior to seeing the actual prime sentence, which they then evaluated as the same or different from their initial guess. This manipulation was intended to explicitly induce prediction and computation of prediction error. They received the other type of prime sentence in a “copying” condition, where they re-typed the prime sentence in a standard repetition priming procedure. Results show substantially greater production of whichever prime sentence type participants received in the “guessing” condition, regardless of the structure of the preceding prime sentence (Fig. 1). This increased production extended to an immediate post-test, compared to a baseline task prior to the priming phase, but did not extend to a delayed post-test conducted 2-14 days later (Fig. 2). Further, participants exhibited no change from baseline to delayed post-test in a grammaticality judgement task that measured their knowledge of grammatical and ungrammatical sentences with TPs in German. These findings implicate prediction as a possible learning mechanism in L2 acquisition but highlight the limits of such a mechanism for fostering longer-term changes in production or learning that extends to the development of grammatical knowledge among beginning L2 learners.

Figure 1. Priming phase: Proportion of target sentences. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Figure 2. Baseline/Posttest/Delayed Posttest: Proportion of target sentences. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

References:

- Alzahrani, A. (2023). What is the next structure? Guessing enhances L2 syntactic learning in a syntactic priming task. Frontiers in Psychology, 14.

- Chang, F., Dell, G. S., & Bock, K. (2006). Becoming syntactic. Psychological review, 113(2), 234.

- Grüter, T., Zhu, Y. A., & Jackson, C. N. (2021). Forcing prediction increases priming and adaptation in second language production. In E. Kaan & T Grüter (Eds.), Prediction in second language processing and learning (pp. 207-231). New York: Routledge.

- Hopp, H., Bail, J., & Jackson, C. N. (2020). Frequency at the syntax–discourse interface: A bidirectional study on fronting options in L1/L2 German and L1/L2 English. Second Language Research, 36(1), 65-96.

- Jackson, C. N., & Ruf, H. T. (2017). The priming of word order in second language German. Applied Psycholinguistics, 38(2), 315-345.

- McDonough, K., & Fulga, A. (2015). The detection and primed production of novel constructions. Language Learning, 65(2), 326-357.

Wh-questions in Romanian Child Heritage Speakers – Investigating the Use of Differential Object Marking and Number Agreement in Comprehension and Production

Anamaria Bentea, Theodoros Marinis

University of Konstanz

anamaria.bentea@uni-konstanz.de

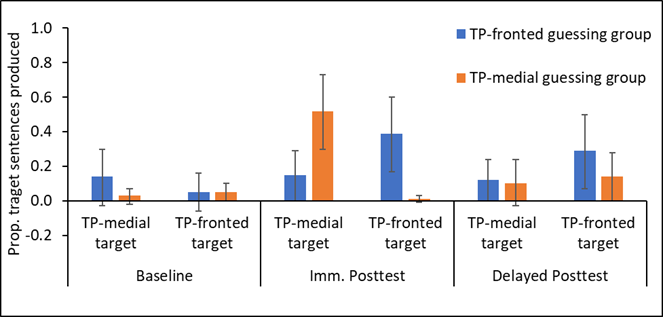

Research on adult Heritage Speakers/HSs has demonstrated that they are highly heterogeneous in terms of Heritage Language/HL acquisition outcomes and typically diverge from monolinguals in their first language/L1 [1-5], however few studies have examined both real-time morphosyntactic processing and production in child HSs. This study compares the comprehension and production of which-questions (examples (1)-(4)) in heritage Romanian and aims to understand whether a. morphosyntactic cues like Differential Object Marking/DOM and number agreement guideonline interpretation in monolingually-raised and HL children and b. whether HL children use these cues in their production. Wh-dependencies in Romanian present morphosyntactic properties that lend themselves well to assessing the use of grammatical cues in (online) comprehension and production: (i)DOM (pe) precedes object wh-phrases; (ii) number agreement disambiguates between subject and object interpretations.

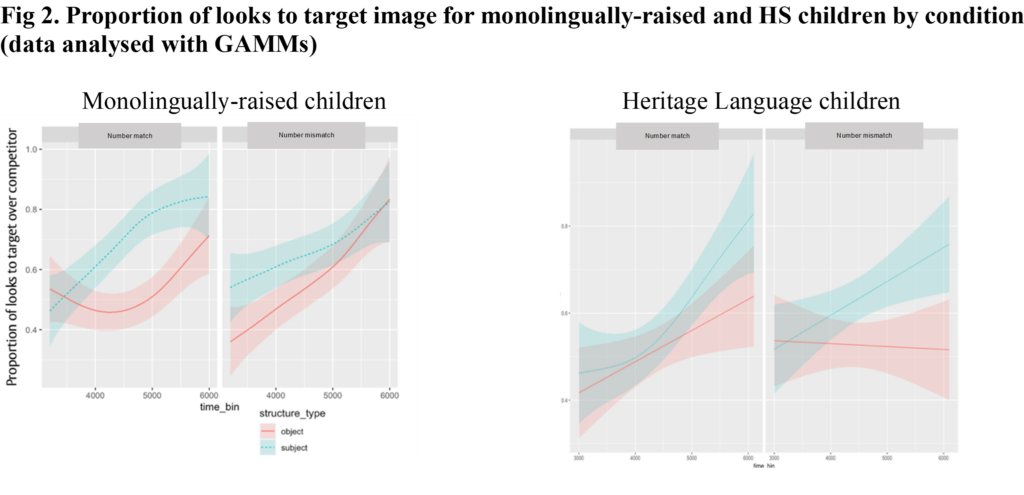

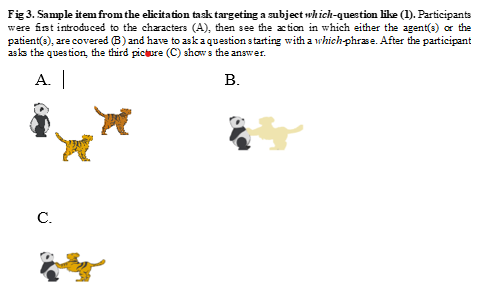

Thirty-one child Romanian HSs with L2 German (5;6-10;0) and thirty monolingually-raised Romanian children (6;4-10;4) took part in a visual-world eye-tracking and an elicited production task (32 test items/task). In the eye-tracking task, children saw pairs of pictures (Fig.1) while listening to subject/object which-questions and had to choose the picture that matched the question. Half the test items contained two singular NPs (number match), for the other half NP1 was plural and NP2 singular (number mismatch). Eye-movements and offline responses were recorded. The offline results revealed significantly better performance with subject- compared to object-questions (p<.001) and an effect of age (p<.01) in both groups, and that monolinguals were significantly more accurate with object which-questions (p=.003) than the HSs. The online results (Fig.2) showed similar processing patterns in monolinguals and HSs for subject questions, which overall displayed more looks to Target images than object questions. The data also revealed a higher proportion of looks to Target in object-questions with number mismatch than in questions with number match, but only in the monolingual group. Fig 3. illustrates the set-up of the elicited production task for subject/object which-questions. The results indicate that monolingual children produce significantly more target subject and object which-questions than HL children. Number mismatch does not seem to enhance which-question production in either group, however significant differences appear in the use of other structures, like bare who-questions, passive object questions and object questions introduced by ‘what tiger’ instead of ‘which tiger’.

Our findings indicate that DOM in Romanian does not eliminate the subject-object asymmetry found with which-questions in children [6]. Moreover, these findings suggest that, on the group level, HS children have more difficulties with the comprehension and production of object which-questions relative to monolingually-raised children. Although number mismatch does not seem to impact offline comprehension in either group, the online data suggest that this mismatch guides monolingual children’s online processing of object-which questions more than DOM-marking on its own. The fact that HS children do not seem to recruit the number information in the online processing of a short syntactic dependency could indicate more protracted processing, e.g., number information is processed after the end of the sentence because of slower processing speed [7].

References:

- Bayram et al. (2021). Current Trends and Emerging Methodologies in Charting Heritage Language Bilingual Grammars. In Montrul & Polinsky (eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics, pp. 545-578.

- Montrul (2008) Incomplete acquisition in bilingualism. Re-examining the age factor.

- Montrul (2016). The acquisition of heritage languages.

- Benmamoun et al. (2013). Heritage languages and their speakers: opportunities and challenges for linguistics. TL 39(3/4), 129–81.

- Polinsky & Scontras (2019). Understanding heritage languages. BLC, 1–17.

- Friedmann et al. (2017) No case for Case in locality: Case does not help interpretation when intervention blocks A-bar chains. Glossa.

- Sekerina & Laurinavichyute (2020) Heritage speakers can actively shape not only their grammar but also their processing, BLC.